One of my favorite panels at PAX East was on “The Death of Print.” In this panel John Davidson, the Editor of the new GamePro, raised a point that has worried for me for some time. Print media seems to be at odds with environmentalism. The UN says that deforestation is “now widely recognized as one of the most critical environmental problems facing the human society today with serious long term economic, social and ecological consequences.” John shared a startling statistic: if a print magazine sells 30% of the magazines that it prints, this is considered a success. That means that 70% of magazines are simply thrown away.

Chris Dahlen, the managing editor of Kill Screen, raised the issue of the magazine as artifact. The problem with an article on the Internet is that you can’t hold it in your hands. You can’t put it in a box in your attic and find it twenty years later, brushing off a cloud of dust and swelling with nostalgia.

I love books. I love the way that they smell and the way that they feel on my thumbs and my index fingers. I love the sound of a page turning and I love lying on a couch with a book on my chest and a lamp behind me. Flipping through Kill Screen and GamePro on the bus to Boston was a wonderful experience – the writing was uncommonly good and I didn’t have dozens of banners and tabs distracting me. If print died a part of me would die with it.

Which is why I struggle with this so much. Sometimes it seems like art and the environment are at odds and I have to choose a side.

The issue is bigger than just print magazines – video games themselves are by nature unsustainable. Computers and consoles have dangerous toxins in them that are often illegally recycled overseas, posing serious health and environmental risks. (Read this.) Playing games consumes lots of energy, and I’ve bought dozens of games, only rarely considering the environmental implications of my purchases. I care about the planet, but I deeply care about games as well. I’ve been struggling to reconcile all of this.

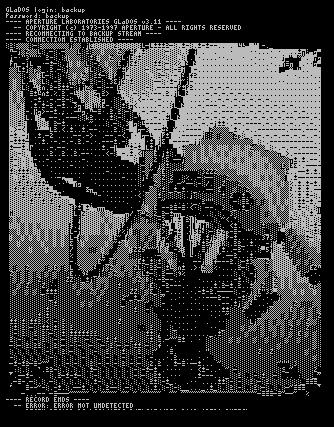

Other mediums like movies aren’t particularly sustainable either, but movies have been vehicles for change more often than games have. Documentaries like An Inconvenient Truth and Exporting Harm (topical – a 2002 documentary about electronic waste in China) have been able to profoundly raise public awareness about important issues. We haven’t had our world-shaking game yet.

A view inside the burn houses where women sit by the fireplaces and cook imported computer parts. Guiyu, China. May 2008 ©2008 Basel Action Network (BAN)

The thing is, I think that we can. Games are an extremely young medium, and we have a lot of room to grow. Right now, the primary concern in game design is whether or not the player is having fun. This isn’t the case in other art forms; many movies, paintings, photographs, novels, and plays are crafted to make the viewer uncomfortable, for instance. Don’t get me wrong, I’m all for having fun, but why can’t we have other emotional experiences as well? Why can’t we have a mystery game where we explore a recycling factory in China?

I appreciated John Davidson’s comment because I’m glad to be reminded that other people out there struggle with these things too. Once a year there’s an exciting festival in New York called Games for Change – it happens in a bit over a month. Unfortunately that’s right before exams, but you should go if you can. Here at Dartmouth, the tiltfactor lab is focused on game design for social change. In the coming weeks I’m going to play a few games that are taking risks and pushing the boundaries of what games might be able to be and write about them here.

So those are my thoughts. I read an article today that deforestation has been on the decline in the past decade – the rate is “remains alarming,” but it’s nice to read good news once in a while. I have to believe that there is a way for video games and magazines to exist in a healthy world. What do all of you think about this?