When I grew up, some games were off-limits. Diablo was a no, because Satan was right there in the title. Grand Theft Auto was also disallowed when my parents caught me mowing down police officers and lines of Elvis impersonators with a machine gun. Mortal Kombat was banned for obvious reasons—you can rip out a man’s ribs and them stab them through his eyes—but even Golden Eye was mysteriously “lost” one day after a particularly hilarious match of only shooting each other in the knee caps. I can understand the logic behind all of these decisions, but I’ve always been confused about why I wasn’t allowed to play The Sims.

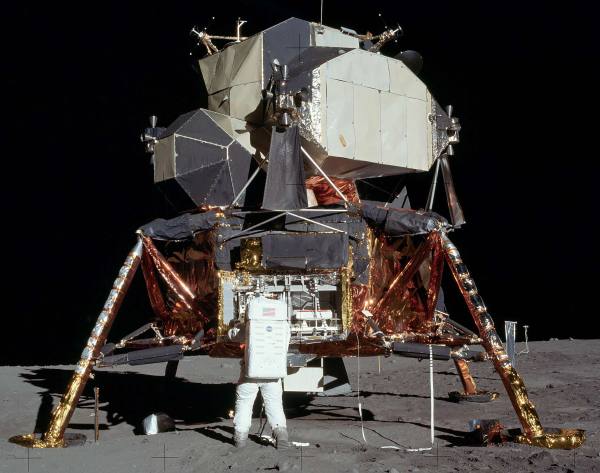

The Sims, for those few of you who don’t know this, is a game about organizing the time of a virtual suburban family. The player directs virtual people, called sims, to interact with objects and individuals in pursuit of their personal goals. One premade family, for instance, is comprised of Jeff Pleasant, who wants to “provide for his family and fulfill his lifelong goal of being the first man to walk on Mars,” Diane Pleasant, who wants to “set her family on its way up the social ladder,” and their two kids, Daniel and Jennifer, who both simply want to “make new friends and succeed in school.” In a game market saturated by violence, The Sims is a refreshing exception. It’s a work of playful satire, and it’s about as far from objectionable as I can imagine. So why did my parents ban it?

Recently I asked my mother about this, and she told me that in her mind, The Sims is a game about controlling lives and playing God. As a Christian, she believes that there is always temptation to try to control your own life, but what God wants you to do is to surrender control to Him. The Sims, she said, gives you ultimate control—it indulges unhealthy and un-Christian power fantasies.

So maybe it’s appropriate that The Sims has an toggle switch for “free will.” If it’s enabled, sims will move without being directed by the player. They will take showers, go to the bathroom, cook food, go to work, call their friends, read a book, all while the player watches through the invisible roof and walls. Left to their own devices, the sims will often make bad decisions. Maybe they’re hungry and they need to go to work in half an hour, but instead of eating breakfast they will just sit and play on their computers, and maybe they’ll skip work. This is the game at its most uncanny.

But that’s not how it’s meant to be played. Even when free will is turned on, direct commands have priority over whatever the sim would otherwise do. The player is meant to micromanage every little part of a sims life in order to try to keep her happy and moving towards her goal. You tell her when to go to the bathroom, when to water the plants, when to hold the baby. A sim will never apply for a job or begin a relationship or have sex without explicit instructions from the player.

I volunteered, once, to speak at a Christian rally in one of the poorest slums of Bacolod, a city in the Philippines. We called them ‘crusades,’ which I found uncomfortable even then. Crusades were missions of mass evangelism and spiritual nourishment—there were skits, songs, testimonies, and messages, and at the end a pastor, accompanied by an encouraging piano, invited people to walk up to the stage and be saved.

I was sixteen and I squinted in the stage lights at hundreds, maybe thousands of people. The microphone felt clammy in my hand as I began to speak. “Imagine that life is a road stretched out in front of you, and you’re in a car with Jesus.” My translator spoke for nearly a minute in Tagalog. He was clearly saying something more or different than my single sentence. When he stopped, I was worried but I continued with my metaphor. “And imagine that you’re a really terrible driver.” My translator began again, speaking quickly and gesturing with the hand that wasn’t holding the microphone. Something that he said made everyone laugh. “Maybe you’re swerving all over the road and you don’t feel safe.” When his hand seemed to swerve in and out of traffic, I felt reassured that we were at least roughly telling the same story. “But the thing is, Jesus is in the passenger seat, and he’s an excellent driver. So you have to ask yourself, do I want to drive, or should I let Jesus drive?” I thought to myself, as I looked out over men and women who had never driven a car in their lives, that I had probably chosen the wrong trite metaphor.

One of the most comforting things about being a Christian was my fervent belief that I could relinquish control of my life to God. “Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened,” says Jesus, “and I will give you rest.” Paul refers to himself as a slave to Jesus Christ, and that was what I wanted to be. I thought that all of my problems were caused by my struggling attempts to control what should’ve been God’s—my body and my mind.

So when I started to suffer from severe anxiety I knew that it was my fault.

In my Junior year of high school I felt ill and so I stayed home from school—at first for a day and then for a week and finally for a month. I went to the doctor almost every day. I had more needle marks in my arm than a heroin addict, because they were taking blood samples almost constantly. I went from specialist to specialist and no one could tell me what was wrong. As I got further behind in school my symptoms got worse, and I then started to have panic attacks. The doctors told me later that I’d contracted a virus which my body had fought off, but my immune system wasn’t aware that it was gone so it kept chewing me up from the inside. The panic attacks were linked to my physical condition, my lack of sleep, and my anxiety over school.

Different people have panic attacks in different ways, but for me it was like this—I lost control of my body and I broke down sobbing wherever I was. At the zenith of my mental deterioration it was happening several times a day. I didn’t ever want to leave my house, or my room, or my bed. Every night I prayed for God to take control. “I don’t know what to do, God, I need to you to show me.” But he never did, and that is when I started to lose my faith.

For that month, games were my way of regaining control and my way of being controlled. I played games that were easy and empowering. Japanese games, mostly. It was comforting to inhabit worlds where I could instigate tangible self improvement, and it was comforting to let those worlds inhabit my mind.

It’s been a long time since high school, and I don’t struggle with anxiety anymore. I do, however, still love the measurable and attainable goals of games. Games are a way to assert control—if not over your life, over the lives of others. If The Sims is about playing God, you’re playing an active, meddling God. Life is a series of small choices, and it doesn’t matter how fervently you believe in him or how thoroughly you want to surrender control to him, Jesus will never make sure that you take a shower before you go to work.

While I no longer believe that I can give control of my life to God, I do believe that it’s important to come to terms with the fact that there’s a hell of a lot that we’ll never be able to control. It’s less scary when you believe that nothing is up to chance, and that everything is a part of some larger plan, but hey—if you ask me, lack of control is what makes life interesting.